L.A. Land of New Beginnings

Alexis Knowlton interviews Ann McCoy

Knowlton:

This is not the first time you and your artwork have been in Los Angeles, Ann. During the years you lived in LA, you had shown your work with Margo Leavin in LA, and with Xavier Fourcade in New York. You won the New Talent Award and were part of Los Angeles 1972 at the Pasadena Art Museum, one of the first LA shows to hit New York.

You left LA in 1977 in order to go to Berlin on the DAAD (German Academic Exchange Service). What was it like to leave LA and hit Berlin?

McCoy:

I loved Berlin from the first moment the plane touched down at Tempelhof. Compared to LA, divided Berlin in January, was dark by four in the afternoon and freezing, with skaters on the ice of Grunewaldsee. I was living behind the Brücke Museum next to the Swedish Consulate, in the old atelier of Arno Braker, one of Hitler’s official artists. There was coiled barbed wire on the road and a guard because the Bader Meinhof had just attacked a Swedish Embassy.

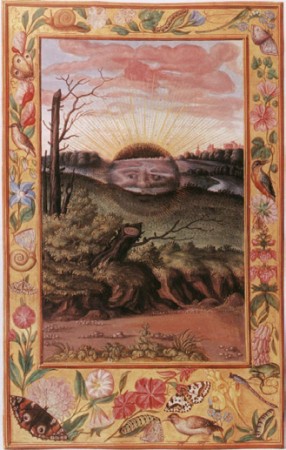

I would go to flea markets with Ed Kienholz to buy Nazi memorabilia for his pieces in his old hand-built Mercedes. Joseph Beuys did his famous Honey Pump piece at Documenta in ‘77, and I met him with James Lee Byars. Beuys, Byars and Eric Orr shared my interest in alchemy. In Berlin, I spent a year drawing the Red Sea, a well known alchemical symbol of the tapis, the heating up of the elemental waters.

I also visited the Pfaueninsel (Peacock Island, near Potsdam) where the alchemist Johann Kunckel had lived and created a rare red glass. Shards of his red glass could still be seen on this site where his glass works had burned. Werner Herzog made the film Herz aus Glas (Heart of Glass) featuring the mysterious ruby glass in that year, but I didn’t know of it until several years ago. In 2008, I returned to Berlin for an exhibition of works related to the fairy tale I had written about the alchemist of the Pfaueninsel.

Knowlton:

How was the art scene of LA different in this time? When I think of LA in the early 70’s, I think of Womanhouse and the male artists of the Ferus Gallery.

McCoy:

LA was very much a boy’s club. As a female artist in Los Angeles, it was easy to feel diminished. I lived on Market Street and had friends like Larry Bell and Jim Turrell, but I was not a part of the Light and Space group. I was the odd duck, my world was complex and baroque in comparison; I did not see life or art in such Apollonian terms. The alternative to the boy’s club was the feminist movement, but this required adhering to a certain iconography and I was a poor fit.

One of the first feminist groups with Eleanor Antin met at my studio in 1971 and was a consciousness-raising group. I was not an acolyte and did not gel with Judy Chicago, who had worshippers instead of colleagues. Channa Horwitz and I were on the outs of the group. Even though I was drawing water, as was Vija Celmins, the feminists did not link water to Aphrodite as I did. I found the consensus on vaginal imagery tedious.

When I got to Germany in 1977, it was the land of Joseph Beuys and the level of dialogue about art was amazing. I felt at home intellectually. I preferred Beuys’ honey pumps and hares to discussions of either vaginal imagery or auto finishes, although LA artists like Wallace Berman and Bruce Conner were wonderful exceptions to this rule.

Knowlton:

I remember the Berliner Zeitung article about your Pfaueninsel exhibition in 2008, when you returned to Berlin. The work describes a fairytale of the death and an alchemical transformation of a king, on the Pfaueninsel. The fairytale takes place during a period resembling the 100 Years War. To me, it sounded like it may have to do with the feeling of never-ending war in America at the end of the Bush years. Did the exhibition relate to this culture of war?

McCoy:

Yes, I wrote Pfaueninsel as a fairytale for our time. I believe that America is still in a dark period where a lot of what we produce wounds and kills innocents. America has soldiers in 133 countries and although we have rapid advances in technology, it has not brought us to a higher level of civilization. We are primitive because we have transformed the outer world but not the inner one. If you speak to someone today about the inner life, the journey of the soul, you are dismissed as a nutcase.

In the art world, we are seeing a decadent gilded age. I see artists not as slaves to commerce, but light bringers, as agents who catalyze a transformation. I am more interested in Occupy Wall Street than Miami Basel. I miss the world I knew of Beuys where art had content outside of the market place. The extreme commercialization of the art world today drives me, along with a number of young artists, into wishing for alternative structures.

Knowlton:

I agree and I think Germany still has more art that is critical of market structures, probably because the market structures, history and lifestyle there is a little different. Can you tell me a bit about primary themes and symbols in your work? You had mentioned that the egg is a cosmogenic symbol, meaning that it generates a cosmos. Can you elaborate?

McCoy:

The egg of the philosophers, the ovum philosophorum, refers to the vessel in which the creation process takes place.

Many creation myths begin with an egg that divides and constructs the world, for example, part of the shell becoming the sky, etc. In this way the egg is the cosmic birth giver, a universal parent. My favorite myth is where Ptah as a deus faber (god as craftsmen) creates the world on his potter’s wheel. Here the idea of god as an artist, and the egg as creation merge in a wonderful way.

In the Kalevala, the Finnish national epic, there is a myth of the world being created from the fragments of an egg laid by a diving duck on the knee of Ilmatar, goddess of the air:

“One egg’s lower half transformed

And became the earth below,

And its upper half transmuted

And became the sky above;

From the yolk the sun was made,

Light of day to shine upon us;

From the white the moon was formed,

Light of night to gleam above us;

All the colored brighter bits

Rose to be the stars of heaven

And the darker crumbs changed into

Clouds and cloudlets in the sky.”

Incubation (a sleeping in) is certainly a part of the process. Incubation was also a healing practice in ancient Greece. In the cult of Asklepius one entered the abaton, a sacred space, to have reparative and prophetic dreams. The egg becomes subject and object for the alchemist who is transforming himself perpetually. At different times and circumstances new aspects of Self and World are born.

Incubation (a sleeping in) is certainly a part of the process. Incubation was also a healing practice in ancient Greece. In the cult of Asklepius one entered the abaton, a sacred space, to have reparative and prophetic dreams. The egg becomes subject and object for the alchemist who is transforming himself perpetually. At different times and circumstances new aspects of Self and World are born.

Decay and rebirth are implied when the egg decays and the bird is born. This is implied in the mystery religions where the seed rots to bring forth new life.

The egg has been present in my work and dreams at different times under different circumstances. These circumstances can be things happening in the outer world or psychological states like depression. Some sort of birth or creative act is always implied. Birth is often paired with difficult circumstances, both personally and in mythology. Christ was born in a stable under impoverished circumstances.

Like Christianity as a religion that began with poor slaves, Occupy Wall Street began with a bunch of kids in tents with no funds. It is these difficult births that interest me. I hope we are seeing a shift in values and consciousness among the youth who are rejecting a culture of greed and war. I had hoped for Occupy Miami Basel, not more jet set parties. The New Orleans Biennial with Dan Cameron, including pieces built in the Ninth Ward by artist like Mel Chin, are more interesting to me than the boring trajectories of art commerce.

Knowlton:

I am not sure if I believe, necessarily, that an “outer world” and “inner world” are distinguishable. When you speak of outer world what do you mean?

McCoy:

It goes back to the idea of the microcosm and macrocosm; the two are connected. What happens in the inner world of the psyche determines fate in the outer world. In modern society, many people see no connection. Cause and effect are thought to exist as externals. We are in the middle of a spiritual, economic, and ecological crisis. Crisis requires the birth of new ideas and these ideas must first come as dreams, intuitions and experiences on the inner plane.

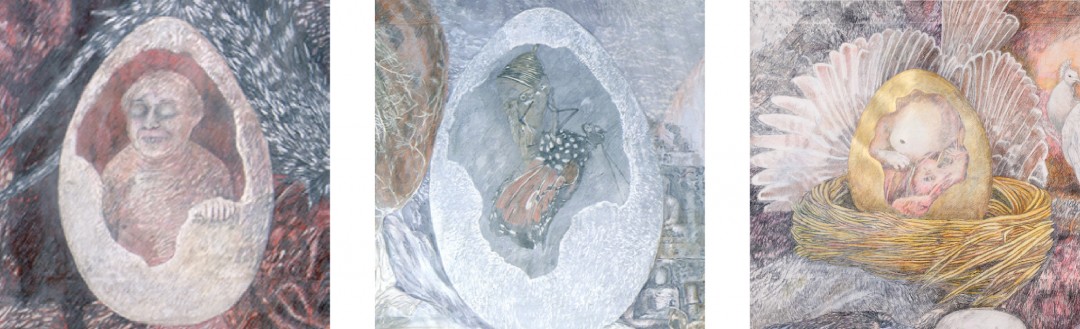

Mad Mother Realm (Detail), Sanctuary (Detail), The Death of My Father (Detail)

Knowlton:

Can you tell me about the three large works in the exhibition: Mad Mother Realm, Sanctuary, and The Death of My Father? The titles are striking.

McCoy:

Each of the works is from a different year and a different period, but they all share an image of the egg as a cosmogonic symbol.

Mad Mother Realm was the first work. I had a dream shortly after my mother’s death where I was in a bloody underworld, not unlike the chamber of horrors described in The Visions of Zosimos, a third-century A.D. alchemical text by an alchemist from Panopolis. My mother was a huge spider with her face reflected in the eyes of the spider, and I am on a slab being sacrificed.

To me, the dream was a signal that parts of my self needed to be transformed, released through an act of sacrifice. I had been caught in a negative mother-complex like the spider’s web. She had suffered from alcoholism, depression, and later dementia. In my own life, I have had to come to terms with alcoholism and depression as well. I quit drinking at 24, but that was just the beginning. Her personality was very rooted in my conscious and unconscious life since mothers are internal figures or imago mater. Dealing with the internalized mother is a problem long after the death of the actual parent.

The egg in the work contains a tiny figure, a homunculus, which represents myself. I am peering out into the world of horror, spiders and blood and am contemplating a birth into this landscape. Blood is related in alchemy to the rubedo, the red part of the process. Here feeling, passion, and spirit enter the process. You drink the blood of Christ in the mass in an act of transubstantiation; you drink the spirit of Christ.

Mad Mother Realm

1999

Pencil and watercolor on paper on canvas

9 by 14 ft

Knowlton:

Sanctuary is a drawing that features a Pieta, a meditating Jina, two children, a dog, a deer, an egg containing a butterfly, as well as other imagery. It is very light in color and far from the bloody carnage of Mad Mother Realm. What went into making Sanctuary?

McCoy:

Sanctuary came from a dream and an experience I had in India. In the dream, I was holding my mother like the Christ in the Pieta. After many years of being angry, I was able to give up resentments, empathize with her suffering, forgive my mother. My mother had a tortured existence with one brother’s suicide and another brother’s death from falling off a cliff. Her life had not been easy. The alchemists said one must give up bitterness, which connects to the alchemical salt.

Sanctuary also relates to an experience I had in the temple of Ranakpur in India, one of the great Jain temples in the world.

The Jains are one of the oldest religions in India. They believe in forgiveness and incorporate it in a confessional festival called Perysiana where all Jains spend nine days contemplating forgiveness and engage in a daily ritual. The experience in the temple could be described as a peak experience. I felt that my inner sanctuary had become mirrored in this outer sanctuary.

The plan for Ranakpur temple had come from one man’s dream. In the Catholic world, the closest example I can think of is Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome. A bishop was told in a dream to build the church where the snow fell. On August 5 in 358 A.D. snow fell in the shape of the cathedral. The temenos, sacred temple precinct, often exists first as a vision or a dream.

As I was finishing Sanctuary, a fawn walked out of the woods into my garden. It was nose to nose with my dog and the tiny deer followed us around for several hours. I became concerned and told the fawn to go back to its mother. The deer followed us back into the forest and then stayed there. I remembered reading that in Irish folklore, fairies ride on the backs of deer. The deer is a creature of the liminal realm, going from the forest to the city garden. I took this synchronic event as a message that I was on the right track.

The butterfly cocoon is like an egg, birth takes place in the cocoon. Before the birth of the butterfly or bird, there is only liquid. It is much like a psychological process, in which one must wait until the process is complete in the container of the unconscious. The birth of the butterfly in Sanctuary is joyous.

Sanctuary

2004

Pencil on paper and canvas.

9’x14’

Knowlton:

You said that the last work, The Death of my Father took five years?

McCoy:

Talk about despair. During this time, I started feeling really disgusted by the art world’s emphasis on prices, auctions and fairs. I had dealers tell me that they couldn’t show my work because of its spiritual content and disturbing imagery. It is fine to put Christ in urine or a drain pipe through the Virgin Mary, but sincerity is regarded as really out of phase. Any discussions of spirituality are relegated to Tibetan art or the safe, historical fifteenth century. I missed the old days of Beuys meetings in churches and at dolmens.

This began to change with a job teaching a crazy art history/mythology class at Yale in the School of Drama to the graduate designers. The class became really popular and is now filled with half fine arts graduate students. I couldn’t get a job in the fine arts, where departments seem dominated by the discourses of third generation October School.

In the theater, the idea of a liminal realm is alive and well. Having a teaching audience again helped me to feel like I could communicate without being censored. I had been fired from the Barnard Art History Department when my class appeared in Keep the River on Your Right: a Modern Cannibal Tale. I had a gay, Jewish cannibal lecturing to students and Benjamin Buchloh fired me on the day of the film’s premiere. It won the Amsterdam Film Festival and was shown at MOMA.

The Death of my Father contains an egg with a fetus. I am a puella, the archetype of the eternal girl or daughter. The work explores my being trapped in a father-complex, attaching and deferring myself to older men through patriarchy. I needed to detach and give birth to myself.

The central image in the work is the peacock, which is a symbol of immortality. St. Augustine believed the peacock’s flesh to have antiseptic qualities and it couldn’t corrupt. The peacock became a symbol of Christ and resurrection and I felt a need for resurrection after a dark period. In alchemical literature, the sun or the peacock often appears after a period of devastation, signaling a new beginning.

The Death of My Father

2012

Pencil on paper on canvas

9 by 14 ft.

Knowlton:

To me, your artwork is a layered and invested drawing process on an epic scale featuring transparent layers of imagery relating to both photography and theater. How do you describe the overlap of process and content here? What is your drawing process like?

McCoy:

I also work in theater, since I teach in the Yale School of Drama and am licensed in projection. For me psychological projection and the projection medium are linked. I have done several large-scale projection pieces like Conversations with Angels, at the museum at Majdanek in Poland. My drawings are on an operatic scale; I love Baroque theater as do many artists like William Kentridge, who utilize theatrical sources like large-scale cartoons.

Knowlton:

It seems like the realms of theater, dream, lived experience and drawing are porous exchanges of meaning in your work. Can you discuss your approach to sculpture?

McCoy:

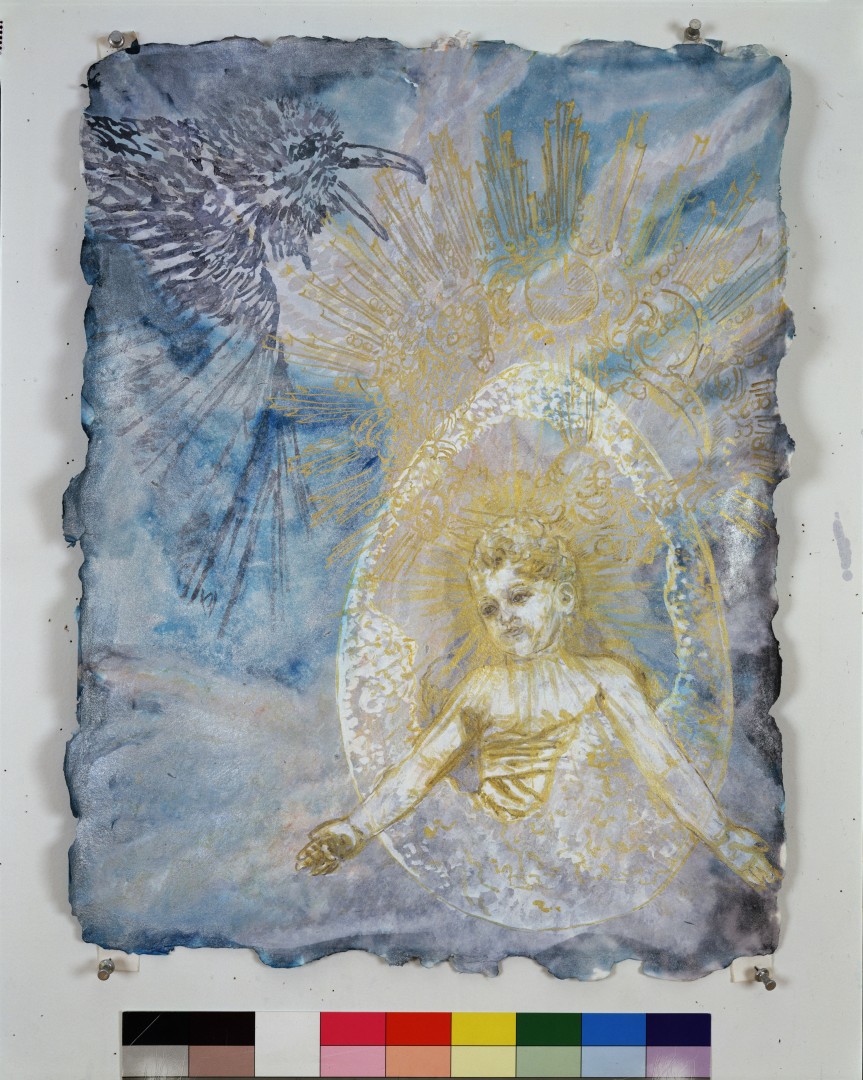

In this exhibition I have one sculpture that I call one of my processionals. I have a similar processional sculpture in a New York collection that features an egg with a silver crown. The processional in this show features a child as a light bringer. Here the child comes from the egg in a new and enlightened state full of hope. In general, like the drawings, my sculpture is narrative and complex.

Processional with Resplendor

2001

Cast bronze with silver crown

19 inches by 7 ft. 2 inches

Knowlton:

Yes, it is, and I am surprised by this gutsy position: how content-rich the sculptures are, especially in comparison to the pervasive normative boycott of theatricality and symbolism in contemporary sculpture.

After reading your texts, I see that you have published writing that discusses, in part, your familial relationships and life. Are you comfortable with your artwork being read autobiographically? What do you think are the limits of an autobiographical reading in your work? Could leaving an autobiographical reading available, especially in the context of a mostly male-dominated critical community be considered a feminist strategy to preserve intentional authority? Or has it simply made you more vulnerable to marginalization?

McCoy:

I love writing by women artists that is autobiographical. I would rather read Carolee Schneemann in the original than any commentary about her work. Carolee, Eva Hesse, Leonora Carrington and many others have written brilliant and personal narratives.

They understand their work and lives better than many (predominantly male) critics.

There is nothing wrong with writing about your own work and life, and for a female artist especially this is a good way to demarcate or own one’s artistic intention. In Carolee’s case, it is difficult to imagine a male being able to broker her pioneering work on erotics.

Artists are myth breakers, tricksters with no respect for boundaries. In the case of women artists, this is doubly true; many of the boundaries that we are trampling over were created by men or reinforce embedded power structures. This fact alone makes men complicated critics for feminist work because the dynamic of a male speaker over a female subject can automatically diminish, marginalize, and distort. Even when the male critic is extremely self-aware, or feminist, the reader still might bring in gendered constructions.

Personal narrative seems to be relegated to literature and taboo in contemporary art. In performance art some personal narrative is returning, but this is the exception. Intimacy and fragility have been crushed by a theoretical and commercial art world that is a synecdoche of the larger world. What we are left with is an emptiness of feeling or an emphasis on the political and sociological that feels barren. My friend Mary Bancroft told me a tidbit she had told Henry Luce to illustrate a point: little kittens were being fed to eagles at the Zurich Zoo. I think that our real concerns and feelings are little kittens that we feed to the eagles of journals like Artforum by paying attention to them.

Knowlton:

That is an extremely painful thought, Ann. It is also difficult not to make gender binaries here with kittens and eagles, feelings and ideas, the visual and the textual. Part of the usefulness of the kitten metaphor, as I see it, is for women not only to avoid feeding the eagles, but to become the eagle. Women would more likely find the cute-kitten-feed tragic, because the female capacity for sacrifice and sympathy is expected, historicized, perhaps biological: see Mary’s sympathy in the Pieta.

In what way does artwork deeply rooted in psychoanalysis, dream, and familial experiences conflict with contemporary models of evaluating artworks?

McCoy:

I want to be a swan more than an eagle, a bird of prey. So much contemporary artwork seems distanced to me and I am not moved by it. It is not simply problems of mechanical reproduction and fabrication, but this is part of it. I see a great potential in outsider artists like Henry Darger who tap into and are committed to an inner life. In my opinion, contemporary art has lost a basic human, or emotionally moving connection. This seems more possible today in drama and literature.

Francis Bacon’s paintings of his lover’s suicide or even Ferdinand Hodler’s works about the death of his mistress are memorable. For me, psychoanalysis opened a door. For example, in the work of Leonora Carrington, suffering and depression allowed her to access a magical realm. In alchemy the sun can appear after a period of devastation. This is true for me and I feel the process can hopefully be mirrored in the outer world, as we face devastation in many forms.

Francis Bacon’s paintings of his lover’s suicide or even Ferdinand Hodler’s works about the death of his mistress are memorable. For me, psychoanalysis opened a door. For example, in the work of Leonora Carrington, suffering and depression allowed her to access a magical realm. In alchemy the sun can appear after a period of devastation. This is true for me and I feel the process can hopefully be mirrored in the outer world, as we face devastation in many forms.

Knowlton:

You are an artist who spent a large number of years seriously studying psychoanalysis in Zurich. This experience might now be described almost condescendingly as artistic research. What do you think of this impulse towards institutionalization and academic validation?

Also, on the reception of your work, do you want your artwork to have exposure to communities outside the art world? What can the art world learn from psychoanalysis or neighboring practices of understanding?

McCoy:

Psychoanalysis made me aware of the language and experience of the alchemical process. It also saved my life and helped me navigate fifteen years of clinical depression without drugs. As I experienced this process in myself, I could understand it better in others. I am a firm believer in the importance of self-knowledge as part of the artistic process.

I saw the psychic process as universal and saw connections to the human experience. Depression is an elevator into depths and through depression, I could understand myths like the story of Jonah and the whale, or the writing of St. John of the Cross and his Dark Night of the Soul.

Knowlton:

Transformation seems like an important word in your artistic process. You have spoken a lot about the kind of transformation that occurs in yourself when you make a work. What kind of transformation does your work demand in a viewer?

McCoy:

That is always a big art historical debate, whether there is such a thing as a therapeutic image. David Freedberg comes to mind. I believe images have the power to transform in an energetic way, which is why I visit certain shrines like the Black Madonna of (in Switzerland).

When I participated in the Hermann Nitsch piece in Prinzendorf, the experience of being bathed in blood in his version of a taurobolium, was truly transforming. Our consumer culture has no transformative rituals like Eleusis or the Apache maiden’s puberty ceremony in which she is anointed in pollen. I like the work of Wolfgang Laib, who is an artist who comes close to a transformative vision of religion by bringing yogis to perform in fire rituals.

Images trigger processes in the unconscious as well; here it is a question of an archetypal image in the unconscious binding to an external image and this is certainly a part of my process as a painter. I hope some inner process in the viewer also connects.

Detail of artist working on The Death of My Father

Knowlton:

I felt connected to something in the presence of your works. That is what had made me originally want to learn more about them. They are totally overwhelming.

My own work lately has a lot to do with translation, and you lived in Swiss-German speaking Zurich for so long. Have you ever had a dream that was too difficult to translate into a visual language? Are your dreams visual or do they also contain other types of sensation? How does representation here both fail and function?

McCoy:

The big drawings come from a series of dreams, often over a long period of time. I try to capture the dream space and its complexity. Sensual experiences in a dream, like an orgasm, are impossible to reproduce. Just as literature has its mediations and limitations, so does an image. The big drawings are usually inspired by a dream local; the other images can appear as I am making the drawing. There is a growth and development in the attention to the sleeping and waking dream.

I am not just trying to match the two up or retell one particular dream in another language.

Knowlton:

Your work is large and dense, at a scale that is domineering, theatrical and intense. In LA, I think about billboard sizes.

Does the scale suggest a powerful will or a desire to coerce?

McCoy:

Life is large and complex. My visual field has always been large. I actually have trouble making small drawings.

When I saw the Diego Rivera murals in Mexico and the murals at the Doge’s Palace in Venice, I wanted to give the inner world the same exposure. Especially as a woman, I think it means something politically charged to bring an interior world into the stage of the operatic, or to make a painting of an individual’s experience at the scale of the physical body, not just the eye.

There is a terrifying power in the idea of a walk-in dream.

Alexis Knowlton is an artist and writer based in Berlin, Germany.